Creating a global buzz, the farmer’s protest in India has gained momentum internationally, but the truth remains that the wheels haven’t turned, and the bills haven’t been amended or withdrawn.

The farmers are still protesting all around New Delhi in the cold weather far from their homes.

What are they fighting for?

The Government of India passed three bills on 27 September, 2020, soon after which the protest started in Punjab, six hours north of New Delhi.

The bills include The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, which seeks to promote open trade throughout the state. It removes the minimum support price (MSP) and lets farmers decide the price they can sell at.

The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020, lets the farmers enter into a legal contract with private entities that wish to purchase the produce. It also has a new mechanism for any dispute resolution amongst the two parties.

Finally, there is the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020, which removes certain essential goods like onions, potatoes, pulses, cereals and oils from the government’s essential commodity list.

These bills in theory are ideal but in reality, the implementation is the root cause of the havoc.

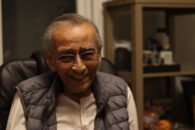

“These farm bills have loopholes that favour the corporations,” says Lovejot Singh, administrator with Ottawa Punjabis, an organization that helps international students in Ottawa. “They provide no protection to the farmers. For example, the farmer cannot take the corporation to court if the corporation fails to deliver on the contract,” says the 30-year-old.

According to the second bill, contract farmers are not subject to a civil court trial. This is assuming that a farmer is educated enough to interpret a contract or has the funds to hire a lawyer, which usually they do not.

The private entity can also demand a certain quality of crop. Failing to deliver would mean that farmers take the loss.

Prior to the bill, there was a minimum rate at which the government would buy the crop and the farmer would make some money, if not profit.

“I come from a farmer’s family,” says Manjot Singh, a graduate of business management and entrepreneurship from Algonquin College. “The low rates, no rebates with no insurance for crops are common issues. These bills will make it even worse. They clearly privatize the agricultural sector in our country where more than 70 per cent of the population depends on farming. We are scared that our lands will be ruled by private companies,” says the 21-year-old.

Private entities can buy the essential goods at a low price, create artificial demand and sell the goods for a greater price later.

According to the third bill, the government will step in only during war, famines and natural calamities to change the essential goods list.

Capitalism in a developing country can cause financial strain on the poor. The third bill in particular will also corner the public into buying goods for a higher price.

What does the protest entail?

“In this protest there are men, women, elders, children, Hindu and Sikh, on the borders of the capital to protect the farmers,” says Manjeet Singh, 21, a student of hospitality and tourism management at Algonquin College.

“My father is a farmer and I have been helping him since I was 14 on the fields. He is out there fighting for his rights in these atrocious conditions.”

The farmers were welcomed with several rounds of water cannons, tear gas and flames.

“They were brutally beaten by Delhi police even though they were protesting peacefully,” says Singh. “To date there are over 200 people who have lost their lives and the government has not addressed it yet,” he says.

“Government is violating human rights at the camping sites. They have cut the internet connections and water supplies and they have barricaded the protest sites so that the farmers cannot have access to the outside world.”

Some journalists have recently been taken into custody and there have been reports of police brutality.

The protestors stay out in the cold, preparing free food for thousands on the site, in the form of the famous langar, a community kitchen with a long history in the religion. The police are offered the same food.

“Think about thousands of farmers sleeping in the cold, away from their families,” says Lovejot Singh, who also organized a peaceful rally on December 5 in Ottawa. “They could have been sitting home celebrating Christmas, New Year. During the pandemic, people expect aid from the government, be it financial, medical or mental, not water cannons, police brutality and barricades,” he says.

“Our goal was to raise a voice on Canadian grounds, but our Prime Minister Justin Trudeau already expressed his concern for the farmers,” says Lovejot Singh. There have been three rallies held in Ottawa. The one he conducted was in front of the Parliament.

Many celebrities, including Rihanna, Amanda Cerny, Mia Khalifa, Greta Thunberg and Meena Harris have also shown their concerns on social media.

With or without the exposure and attention towards the farmer’s protest, there has been no favourable response from the Central Government of India.

Sovereignty in India bars the rest of the world’s authorities from meddling in the situation. Only democracy and the people of the nation can peacefully win over this crisis.