Most students spend their summer worrying about school, finances and OSAP.

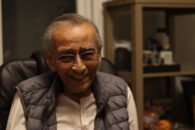

Not so for Zubair, the Kashmir native who seemingly had it all laid out for him.

His co-op was going well, he was accepted into an Ontario university and even won a scholarship.

Everything was going well until Aug. 4, 2019, the last day he spoke to his family.

Zubair, whose name we have changed due to safety concerns, is not unfamiliar to instability.

Indian-administered Kashmir, claimed by both India and Pakistan, had seen its share of conflict since it became a state in 1947, following the partition of British India which divided the land mass into two separate nations.

In fact, the Indian Constitution even had a special provision for the Indian-administered Kashmir, Article 370, which granted the region autonomy over its own internal affairs.

So when he called his family on Aug. 4, as was his near-daily practice, it wasn’t unexpected that he would hear about some of the issues that plague the region.

His family informed him that there had been an increase in the number of Indian troops sent to the region and all non-Kashmiris were ordered to depart the region by the Indian government.

“I was completely shocked and worried that something really wrong was going to happen,” says Zubair.

And if something wrong had happened, Zubair wouldn’t have known.

The following day, the Indian government implemented a communications blackout in the disputed region and he had no means of contacting his family.

In the days that followed, Zubair would come home from his co-op, head to his room and frantically try to get in touch with his family.

However, when the line connected, it wasn’t the familiar voice of family greeting him on the other side. Instead, it was a pre-recorded voice saying: “The number you are trying is switched off right now, please try later.”

Sometimes in English, sometimes in Urdu and sometimes in Kashmiri, but the same message nonetheless.

WhatsApp, Facebook, cellphones and landlines — nothing worked.

Furthermore, the Indian government announced that nearly all of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution had been revoked, effectively stripping Kashmir of its autonomy and adding to Zubair’s concerns.

Zubair tried desperately to contact his family over the next several days, to no avail.

“The first few days, I used to send bulk messages to all my relatives,” he says. “I ended up with a high bill, but nothing. No reply.”

The lack of news from his family affected his focus, his concentration and his emotional well-being.

While driving to his co-op, thoughts about his family would crash down on him.

BEEEEEEEEP. The horn of a car coming behind him temporarily brought him back to his current situation. He had almost crashed. In fact, he had several more near accidents that week.

As time went by he became more desperate, looking for different means to contact his family, including sending a message through a person who traveled to the region.

“Someone traveled to Kashmir, I sent him my voice note on WhatsApp and told him to share it with my family and get a voice note from them, but I don’t know anything,” says Zubair.

“He didn’t return anything so far, it’s been two weeks already.”

His worries took a toll on his academic planning.

Despite being accepted into his school of choice and receiving a scholarship, he decided not to attend the fall term.

He just wasn’t in the right state of mind.

“I can’t do anything. I can’t focus on anything. It’s always in my mind, ‘Are they ok?’” says Zubair, while explaining how his worries have prevented him from further pursuing his academics.

“It’s so depressing,” says Zubair. “I try to sleep. I lay down at 1 a.m. and I fall asleep at 5 a.m.”

Zubair’s work life was also affected. He would sit in front of the computer in his office trying to complete his daily task. As he stared at the screen, thoughts and images of his family would fill his mind, overpowering the images on the monitor.

Jobs that he used to be able to complete in two hours now took four. Jobs that would take four hours now took eight, and so on.

When possible, he would do conferences over the computer to avoid human interaction.

“I’m still in my co-op. My manager, I explained to her the situation. She is flexible with me,” says Zubair, adding that she allows him to work from home some days.

There are many others in Canada that face situations like this. Stuck in a legal limbo with nowhere to go and hostile situations in their native lands, they are essentially stateless.

Though refugee, humanitarian and compassionate grounds claims provide an avenue for some people in these situations, there are often obstacles in the way.

In Zubair’s case, he doesn’t want to leave his family behind.

He doesn’t speak openly about what is occurring for fear of being deemed as “outspoken” and the repercussions such an action would have on his family in Kashmir.

He also worries about the risk of having his passport revoked, as travel documents for people from Indian administered Kashmir are issued by the Indian government.

For others, seeking to make Canada their permanent home by applying for status via refugee or humanitarian and compassionate grounds is a viable option.

It is easier said than done.

According to Statelessness in Canada, a paper researched and written for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, humanitarian and compassionate grounds applications can take 18 to 24 months to process and even longer in some cases.

“If they’re awaiting determination of status, there is uncertainty and anxiety that comes with that,” says Fareed Khan, human rights activist and director of advocacy and media relations for Rohingya Human Rights Network.

In the case of Zubair and the fear of repercussions, Khan says that such cautions are not unwarranted in many situations.

“That’s a very real concern of people, whether people in Kashmir, Uyghurs and others,” says Khan. “People who speak out, they speak out anonymously.”

Compounding on the feeling of uncertainty is the fact that, according to Statelessness in Canada, applications based off of humanitarian and compassionate grounds are discretionary and, “While statelessness is one factor in consideration (among many others, including establishment in Canada, family ties, best interest of children, admissibility issues including criminality), statelessness is not determinative of the decision.”

With no guarantee of acceptance, an everchanging political climate in his home country and concerns for his family’s well-being, Zubair has taken solace in isolation.

“I spend time by myself, or I read Quran,” says Zubair. “I like to code. I take the frustration out on coding, which is not productive at all, but I’m not seeing anyone [counsellor etc.].”

This is something that education professionals say is common for people in these positions.

“Mental health is one of the biggest challenges refugees and people coming from troubled regions face upon arriving to Canada,” says Nadia Alakoozi, an ESL teacher who has taught people from many war-torn and struggling nations.

“A lot of times people from conflict-ridden areas carry unseen wounds from the trauma they’ve experienced, or the instability they’ve lived through.”

She also says that culture can sometimes be a barrier to seeking treatment.

“In some cultures there, things like this are taboo to talk about. There’s a stigma attached to it, so unfortunately people suffer in silence.”

And for those willing to seek treatment, including students, their immigration status may be a barrier to treatment.

According to Statelessness in Canada: “Stateless persons without a permanent residency, and thus no access to health care, may be forced to resort to ‘back alley’ treatment, or perhaps treating themselves or not receiving any treatment.”

Khan acknowledges this as well, stating that for newcomers to Canada without permanent residency or citizenship, sometimes the only support comes from their respective communities and community organizations.

This is something of which Zubair is aware.

“Members of my local community always support me. Some brothers invite me for food, but I don’t like to go. I like to be by myself,” says Zubair.

He says that the stress from the situation has impacted his social life to the point where he ignores messages from friends and avoids social gatherings as much as possible.

For him, he won’t feel better until he knows his family is ok.

“I don’t think anyone can imagine what I am going through. I can’t express that in words.”

This is how Zubair spent his fall semester. During a time when other students are buried in books, he was buried in worries. Instead of studying for classes, he was researching methods to get around a government-implemented communications ban without help, guidance or a country of his own.

Stateless.

Since the time of writing this article, Zubair has been able to get a hold of his family. On Oct. 14, 2019, the Indian government restored some service to cellphones in Kashmir, though Zubair states he sometimes has to call 20 times before the call connects.

He adds that he would like to attempt to start school in the winter semester, but the situation in Kashmir is still unstable. The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019 took effect on Oct. 31, 2019, and effectively redrew the boundaries of Indian-administered Kashmir. Zubair says if there is another communication blackout or increase in instability he will have to put a hold on his academics, yet again.