The startled polar bear charged out of the lake, water streaming off its back, on the outskirts of Churchill, Man., chased by a helicopter. Nisar Hussain was waiting for this precise moment, ready with his camera. CLICK! But the elation was ephemeral as the realization struck — the beast was headed straight toward him at full gallop, less than 20 feet away. Hussain stumbled backwards and fell into a ditch.

Someone must have been praying very hard for his safety, for the wild animal chose to ignore the easy target and sprinted straight past into the forest.

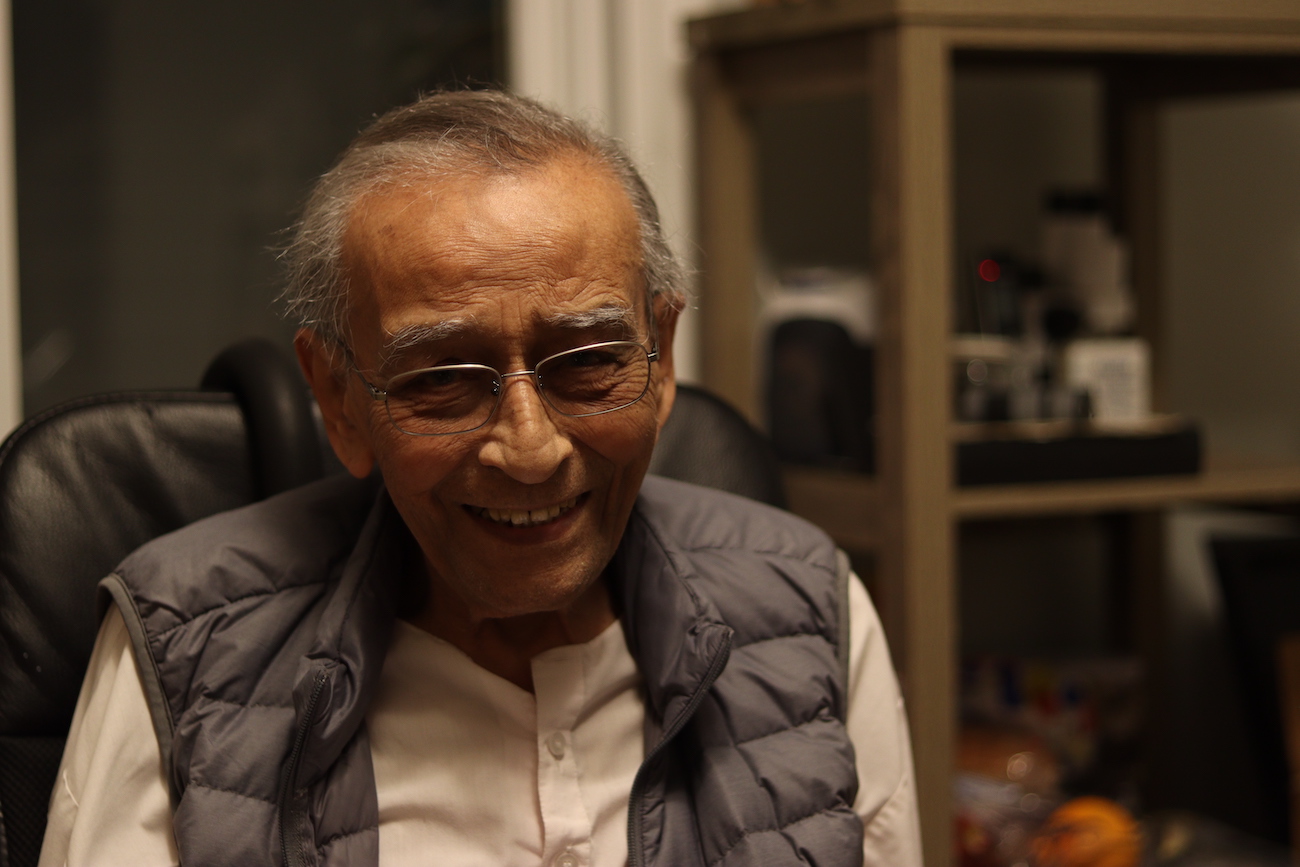

At 93, Nisar Hussain has lived a full life. Look deep into his wrinkled face and you see friendliness and kind, welcoming eyes. He speaks softly and deliberately. His hair still has streaks of black in it, and while his hearing isn’t what it used to be, his mind is as sharp as ever. A walking stick is slung over the back of his chair. Dressed in a sleeveless puffer jacket over loose white clothes, Hussain peers over rectangular wire-rimmed spectacles.

Chatting with this calm and composed gentleman at his home in a quiet neighbourhood in Kanata surrounded by family, you wouldn’t imagine you were speaking to a former operations officer of a rocket range way up in Churchill, Man. Five decades since that adventure, he still hasn’t lost the twinkle in his eye and enjoys a good conversation.

Hussain is from India, and before coming to Canada in 1965, he was in the Indian Air Force for over a decade, starting as an adjutant and working his way up to squadron leader. While age has hunched him over, he retains the disciplined poise of someone who has served.

He must have been good at his job, because when he decided to leave, no less than India’s president at the time, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, tried hard to talk him out of it.

“Just tell me what you want and you’ll get it,” he recalls Radhakrishnan saying to him. But after 13 years of service, Hussain had grown tired of his work and wanted a change. “In India, even the air marshal, field marshal or general of the army can’t buy a second-hand Chevrolet. He can’t afford it,” says Hussain. “Whereas in Canada, every Tom, Dick and Harry has one.” The memory makes him chuckle and he admits he can be flippant.

Appeals from his superiors did not work. A cousin had recently immigrated to Canada, and so Hussain decided, at the age of 36, to move to Toronto with his wife Aalia and two children — Zahra, nine and Irshaad, six.

There was no certainty, only probability, but Hussain was optimistic and hopeful. He had faith that it would work out.

“I sent out almost 300 applications,” he says, reminiscing about his first months in a foreign land looking for a job. But he kept getting the same answer — that he had no Canadian work experience. Finally, an aircraft company gave him a shot, and even though it was boring, he stuck with it.

His patience was rewarded when he got a call from the National Research Council a few months after he arrived, and was flown to Ottawa for a meeting. At the end of the long interview, when asked if he had any questions, Hussain, genuinely intrigued at this point, asked, “You’ve been talking about rocket ranges. There is nothing in my resume which says I know something about rockets and telemetry and weather. I just want to know why you wasted taxpayers’ money and brought me here?”

Hussain’s brevity and honesty would set him apart from his peers, and people recognized that. The director of the NRC at the time later said that the moment Hussain told him off like that, he had the job.

By October 1965, Hussain had moved to Churchill, Man. with his family as operations officer of the Churchill Rocket Research Range.

*************************

“They used to have helicopters during the day that would patrol the Fort Churchill area to see if there were any polar bears coming into town,” says Irshaad, Hussain’s son, recalling his time in Churchill as a child. “And if they did, they’d tranquillized them and took them out of town.”

Hussain wasn’t expecting much when he landed in Churchill. But he loved how everyone employed at the rocket range had a three-bedroom house. “Didn’t matter if you were a boss or a sweeper, you all got one house. This is real democracy,” he says.

The homes were connected to each other via insulated corridors, and U.S. army-issue parkas were provided for the bitter cold. It was a small, tight-knit community. So small that you didn’t dial phone numbers to reach someone. You merely picked up the phone and asked the operator to connect you.

Irshaad remembers how they were interviewed soon after they got to Churchill. “Any new person who comes to Churchill, they put them on TV so everybody knows.”

But it was beautiful, they agree. All along Hudson Bay is a beach and then almost a kilometre of smooth glacial rocks with crevasses that you can leap between. It was the perfect playground for kids.

And then there were the polar bears. The easiest way to see them was to just drive down to the garbage dump, where they would be feeding. They would walk up to car windows, remembers Irshaad, and curiously inspect the interior before returning to the garbage.

But they would end up around people’s homes, too. There were no freezers in the houses. Instead, families would have a wooden chest outside because it was so cold. And the bears would come for that, sometimes getting bold and breaking windows to get in the houses.

Rockets in the sky

Hussain would travel to the U.S. often on work trips. On one of his first visits, when the customs officer asked for his purpose of travel, Hussain’s sense of humour got the better of him. “Veni, vidi, vici,” he replied — Latin for “I came, I saw, I conquered.” His luggage was promptly taken to the side and keenly inspected. But the incident still makes Hussain laugh and he doesn’t regret it.

At this point, spacecraft and airplanes would fly through the aurora borealis — the northern lights — but they weren’t sure what sort of radiation was coming through due to it. One of the main projects the NRC was running during Hussain’s time was to understand this better. They would launch rockets loaded with sensors straight into the natural light display and record copious amounts of data. Some rockets were designed to explode to see the effects. Scientists from all over the world would come to use the range.

But Hussain admits he “didn’t know anything about anything” when he first arrived. He spent the first week just getting to know the people running the different departments and absorbing as much as he could. He learned of the obscure potential the equipment had — the radar could track a baseball 3,000 miles away. And the people he met were all too happy to show him around.

Soon, Hussain was presiding over pre-flight meetings in addition to all his other duties. He remembers the time German scientists came over to run some experiments. They launched a rocket that exploded and spread barium all over the sky for hundreds of miles. “Next morning I went to the office and the phone didn’t stop ringing from the airlines, which were flying transatlantic saying they saw UFOs,” he says.

All this would keep him constantly on his toes, regularly working 18 hours a day. He would head to the range in the morning, work till 1:30 p.m. and come back and sleep. Then it was back at 5 p.m. and work till two in the morning.

Time to move again

After four years in that harsh and unforgiving environment though, Hussain and his family had had enough. “I never understood how people chose to live in Churchill,” says Aalia. So in July 1969, the Hussains packed up and flew to Ottawa for a quieter life.

For Hussain, it was just another move and another opportunity to learn something more. When he came to Ottawa, he was made Secretary of the International Committee of Space and Geophysics.

From the Indian Air Force to moving to a new country and then learning how to run a rocket range in one of the harshest places to live in on Earth, Hussain maintained a positive attitude that always saw him through situations that would daunt most people. He thinks long and hard on what set him down that path. How did he manage to achieve all he did?

An hour later, Hussain has an answer. It all goes back to a school teacher, Mr. Daniels. “He used to quote the Bible verse ‘Ask and you shall receive’ all the time,” said Hussain.

“So whenever I didn’t know something, I would ask.”