It was my job to sweep. It wasn’t too difficult to do, even for a 10-year-old. I had gotten better over the years. I used to watch my mom do it, fast and swift as if part of the allure. She had the perfect technique. One hand down around the middle of the handle, her forearm guiding the bristles around her two black, shiny styling and sink chairs.

The foil women hardly noticed, keeping their pampered noses up, only seeing their reflection in my mom’s giant square mirrors hiding our beige walls. Her long, black apron swung as she swept locks into the dustpan that she’d kicked up with one foot. Her other hand blow-dried or untangled.

I wasn’t nearly as good as my mom was. But the foil women liked to pause from their gossip to comment on how cute I was or – if they’d been coming long enough – how much I’d grown. I was small and slow, but I got the job done for the most part.

The smell of the bleach processing in Annette’s Goldwell hair colour or the familiar stink of matante Germaine’s perm seemed to say that this place, the busy corner of the first floor of our home on Main Street, was a place of business and of getting things done. Sweeping was my tiny role in what seemed like a huge enterprise. My mom always reminded me that the floors had to be cleaned for each new client, no matter how little hair or dust.

Maybe it was in the manuals she studied before she graduated from beauty school in 1993 and won four trophies of excellence. Or maybe it was one of the ways she showed her pride in her place, her livelihood – our livelihood.

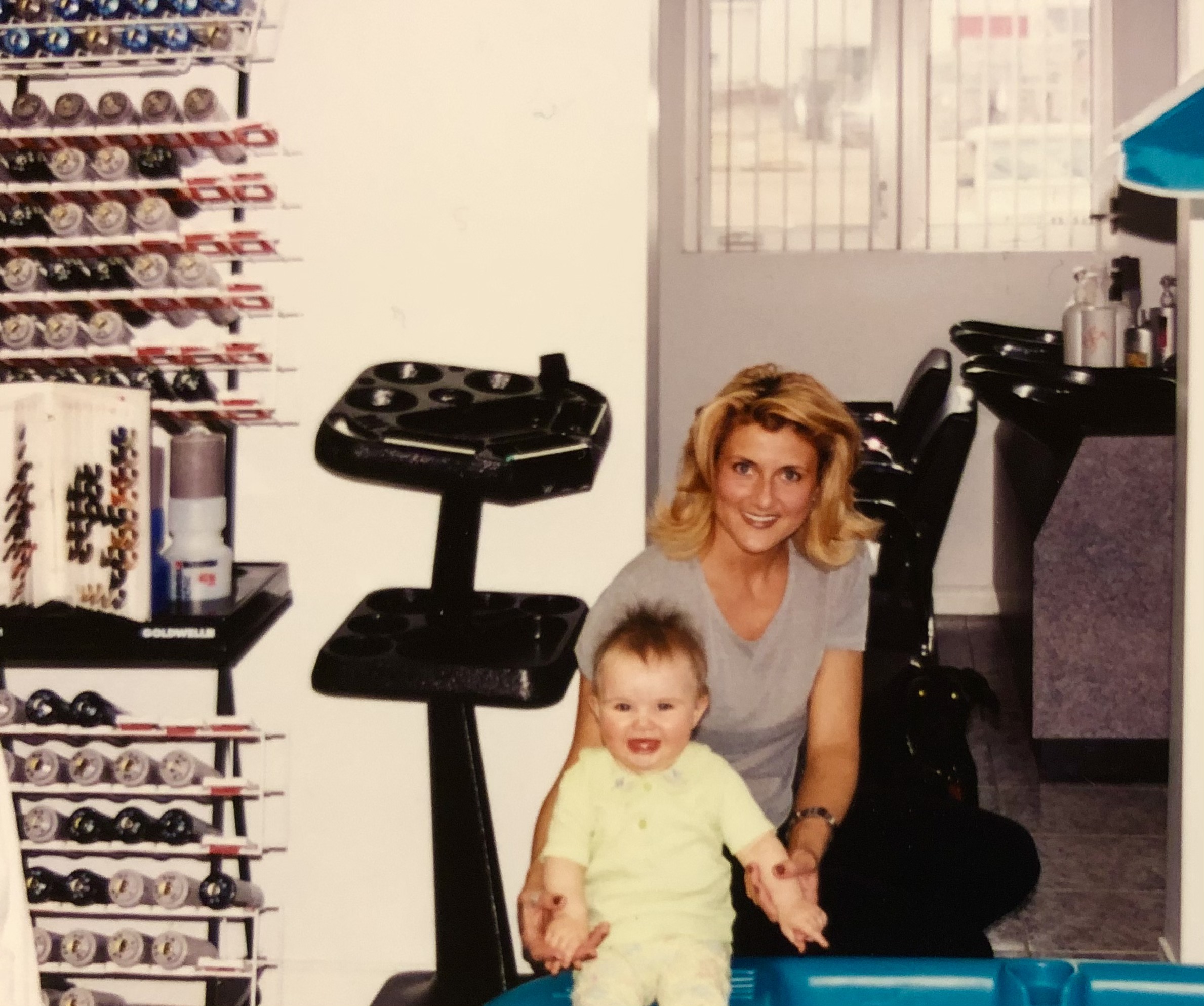

Graduating from beauty school in 1993, Jackie Belliveau's best hairdressing skill was mixing and applying color. It was also what she loved to do most. Photo credit: provided by source

The sign went up before my time on the front lawn in 1996 between the two big maple trees. It was a wooden maroon sign with detailed trims that read Distinct Hair Design – Unisex. In no time, it was known in Shediac, N.B. as the salon in the pink house – a ’50s Pink Ladies jacket shade of pink.

To this day, she says what she misses most about being a hairdresser are the clients. Some were mothers and grandmothers; others became friends that would demand cracking open a bottle of wine after all the hair cutting was done on a Friday night. A few were fierce local businesswomen. Even fewer were those that worked for the federal government in town.

A sort of prestigious process bred these public servants, tested and tried and trained to get into a pool that would get you into a smaller pool that led to a smaller pool. My mom needed a change. A change that would bring greater pay and a future in the form of a pension.

She hadn’t gone to school in over 17 years. Regardless, she decided 2009 would be the year she’d go back.

Her clients, the very few that worked for the government, told her that to get in meant adding a business administration diploma to your resume. My mom had nothing of the sort. She had 13 years of maintaining a client base, running books and a business, but that wasn’t a diploma from the Atlantic Business College.

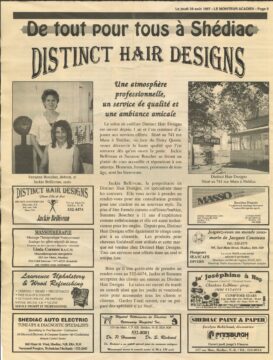

An article from Le Moniteur Acadien on Aug. 28, 1997 features Jackie Belliveau's salon, Distinct Hair Designs, in Shediac, N.B. Photo credit: provided by source

The Jeep my mom owned in 2009 was red like wine. It was a boxy, two-door warrior that had brought us just about everywhere. Its tires were worn but they still turned on a dime. It rolled just as fast that year on Highway 15 from our house to the college when my mom packed a backpack and chose to start again in January.

She went up every morning, Monday to Thursday for the compressed five-month course. When she’d drop her accounting books on the table every night, she’d spin into her apron and reunite with the foil women. She tells me now that she had kept the clients she didn’t have the heart to give up and worked every Friday and Saturday morning.

My parents separated when I was an infant. By the time my father dropped me off before supper, she had done more than most.

I don’t remember much from back then, switching homes on a schedule, seeing my mom run in and out of the kitchen while the foils processed to mix the tomato sauce for my dinner.

But I do remember that Jeep. It had a simple radio dash with a silver nob. It could blare out music like you wouldn’t believe. It would turn heads when you passed cars on the highway, so loud they could almost tell what you were playing. My mom made it an unspoken rule that music was only good if you couldn’t hear yourself think.

But when she blared music that winter in the Jeep, it was almost always the same song. “The Climb” by Miley Cyrus was released that year. Probably named so for my mom’s drive to the college. By the second time she heard it, she had the lyrics memorized.

The song is about keeping faith in the path laid out in front of you and recognizing the climb you are on while you are on it. My mom doesn’t really believe in coincidences. So, for her, to this day, that song is what kept her climbing.

By the end of her term, the only thing left to complete was a job placement.

The college usually set up different opportunities for its students. That is, until they had my mom as a student.

She remembered what made her want this change in the first place and she was not going to settle for anything less. She was going to get her foot in the door at the federal government.

The college’s placement coordinator told her she would never have a chance of getting in there, that it was just too difficult. When my mom tells me this story now, her left eyebrow still cocks to ‘watch me’ heights.

Two years later, at a restaurant on Shediac’s wharf, she saw the placement coordinator. She walked up through the crowd to her table and said, “Guess where I work?”

She had gotten hired a few weeks after her placement at the Government of Canada Pension Centre. The coordinator said she must have gotten lucky, and my mom walked away. That day is one she says she’ll never forget.

When you’re 10, you don’t appreciate what it means to go to school all day and work all night. When you’re 10, and you attend your mom’s college graduation, you don’t realize how impressive it is when she graduates with honours and goes on to get a fourth promotion at the place she was once told she would never get into.

You don’t realize that seeing your mom grow meant that you would be able to soar to heights you couldn’t have imagined. I still don’t know how to begin to thank her for continuing to climb into that Jeep.

Today, our house isn’t pink anymore. I haven’t seen any of the foil women in years. I don’t think they would recognize me if they saw me.

The walls that held my sweeping grounds for 13 years have been knocked down. But if I try hard enough, I can still imagine the way it was. I don’t know whether my broom is tucked away in a dusty closet or in the cluttered basement. Maybe it was thrown away.

I’m not sure that I’m ever going to be as good a sweep as my mother was. But I do know that I’ll keep trying to be even half the woman she is today.