Imagine walking down a straight and narrow path, which then begins to disappear and crumble beneath your feet. What was once a firm and solid foundation has now gone and vanished into thin air.

Panic starts to overwhelm, and the few ways leading back to peace of mind are hazy and unclear.

The news of pregnancy can evoke more than one emotion.And for some, deciding on what to do with that news can be difficult, especially if they need to decide it on their own.

One in three women in Canada will choose to have an abortion, according to a 2012 report in the Contraception Journal.

Yet right now there are limited medical resources for women seeking support on and around abortion, especially if they can’t turn to friends or loved ones in fear of shame or judgement.

There are simply not enough providers to perform abortions to fit the need of Canadians across the country, especially in smaller communities. According to abortionincanada.ca, only 16 per cent of Canadian hospitals perform abortions.

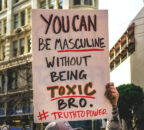

Due to stigma surrounding abortion, some doctors may choose not to perform the procedure at all, in fear of being labeled and stigmatized themselves. Fear of backlash and anti-choice groups could also play a role in the lack of willing providers.

Abortion itself is a health care choice that doesn’t have to equal trauma. Seeking support and reaching out to people can be the challenging part.

More times than not, women choose to hide what they’re going through rather than risk shame and judgement from family and friends.

Because some women have problems locating a willing practitioner, the time it takes to wait for a procedure pushes further into the gestation period, forcing an unwanted pregnancy to carry on further than intended.

Not only do the insecurities continue to grow, but the mental toll can be detrimental to some.

Shannon Hardy, of Nova Scotia, knew there was a significant need for these women out there and felt obligated to help. After six years as a birthing doula, Hardy’s knowledge on women’s reproductive rights grew, and so did her passion to want to change things. This was true especially when she realized the lack of abortion coverage in most provinces, and that Prince Edward Island hadn’t started performing abortions until 2017 over 34 years since the last one had been performed.

Much like a birthing doula assisting women in giving birth, an abortion doula serves women going through an abortion. The role is to become a support system before, during and following the process. Each job is specific to whatever the client needs, whether it be a phone call for support, locating a service provider or help in arranging appointments.

Hardy co-founded the Nova Scotia Doula Association and she founded the Abortion Support Services Atlantic in 2012.

“All I could think was how are people accessing [services], or how are people getting to Halifax or Moncton [if they need to travel out of province to get the support]. How do people navigate that? That’s ridiculous,” says Hardy. “Somebody needed to do something, and my mom used to tell me I was somebody, so I just did it.”

A research study was conducted in 2017 by the University of Ottawa regarding women seeking post-abortion support. It found that there was a disconnect between women’s desires for said services and what is actually offered. Women consistently reported difficulties in accessing low cost or free, non-judgemental, and confidential support.

“We are all facing the same issues around access,” says Hardy. “Regardless of what province I’m in, we all talk about the same things. We get to talk about the access problems across the country and they’re all the same.

“I do trainings in both Corner Brook and St. John’s, N.L. Corner Brook is where all the nurses go to school, they have beautiful new facilities, it’s where people have their babies.”

Although they have the equipment and staff needed to provide abortions, women have to travel roughly seven hours across Newfoundland to go to the one clinic in St. John’s.

This past summer, a group of volunteers took steps in Hardy’s directions and decided to open their own collective of abortion doulas in Ottawa.

The Ottawa Abortion Doula Collective, a volunteer group of seven women, launched in May 2019. The goal was to be the first point of contact for those looking for support in the Ottawa area. They know from experience which providers are best to go to and they know the process inside out. Their hope is to be a top hit on Google when searching for abortions in Ottawa, despite having no federal recognition or government funding

to back them.

“In Canada, it’s not like we’re pioneers, but almost,” says Ottawa Abortion Collective doula Julie Vautour.

“Abortion is health care, it’s not an alternative way, it’s not a contraceptive method,” she says. “Abortion is health care.

“We need to keep talking about how you’re taking responsibility for your health by getting an abortion,” she says.

Vautour believes there’s a gap in the services offered and the actual support that someone may need. It’s the little things that one wouldn’t know about until they’re in that position themselves.

“If someone’s pregnant and they know they want to get an abortion, where do they even begin, where do you start?” says Vautour. “It’s so complicated.”

The majority of the people who have sought the Ottawa doulas’ help so far have been those who have had no support system, or person(s) to lean on at home.

In most cases, family physicians and gynecologists often act as abortion providers. However, training for abortion is rarely considered routine in most educational programs. Most doctors seek outside guidance and mentorship for learning how to perform abortions.

“Stigma is deeply rooted in the medical system itself,” says Hardy. “If you’re a doctor and you want to learn abortion procedures, it’s generally not taught in medical school.”

Abortion is not always talked about in high schools, post-secondary institutions and, remarkably enough, even in medical schools.

“Somebody could go their entire school lives and not hear anything about abortion, in health class or sex-ed,” says Hardy.

“At St. Martha’s, here in Nova Scotia, in Antigonish, you aren’t allowed to talk about abortion if you work there, it’s a Catholic hospital,” she says.

Doctors employed at Catholic hospitals in Canada are not allowed to perform abortions. Discussion around abortion is looked down on. One in every 10 Canadian hospitals is Catholic.

In Canada, it’s up to each province to come up with its own mandated policies for hospital and medical staff, as per the needs of each province’s citizens.

In Ontario, the nursing profession has been self-regulating since 1963.

The College of Nurses of Ontario gives guidelines to all nurses who work in the province. Those guidelines provide standards for maintaining nursing practices, conducting reviews and establishing the competencies required for the nursing practice.

The guidelines consist of 79 entry-level competencies summed up into five categories. The words abortion or termination are not mentioned once overall.

However, how to maintain a proper social media profile can be found in Foundations of Practice.

For nursing students at Algonquin College, the topic of therapeutic abortion as a surgical procedure is not discussed since students don’t attend placements in that specialty area, says nursing professor Susan Eldred.

“The topic of abortion is used as just one of many examples to frame discussions about values, conflict, ethical distress, nursing accountability and responsibility and conscientious objection,” says Eldred.

Sophia Bigras, nursing professor at the University of Ottawa, says she also doesn’t cover abortion specifically in her lectures.

“I do have one case study related to that issue that we discuss during group discussion,” says Bigras. “We might spend 20 minutes on that case study. The girl is a minor who gets pregnant. Her parents were aware that she had a hereditary condition but never told her, thinking she was too young to get pregnant. Now that she knows, one option she faces is abortion.”

Whether it be more discussion in school settings or in everyday life, the talk surrounding that choice should empower the woman making it.

It would help the one in three Canadian women who makes that choice to feel less alone.