It was no different than any other Thursday afternoon in the fall semester of 2014. Tim Hickey, a 19-year-old student at the University of Ottawa, decided to procrastinate when he should have been studying for his second-year communications exams by researching an outlandish subject. The provincial wrestling coach melted into his couch at home and typed into his Google search bar “kidney donation and reception.” He has no recollection of what propelled him to explore this subject, but after becoming entangled in a web of online kidney transplant forums until he couldn’t see straight, he picked up the phone, called the Ottawa Hospital and embarked on one of his life’s most remarkable journeys.

“Hey, can I donate my kidney?” Hickey asked the Ottawa Hospital receptionist who picked up his call that day in 2014.

What had initially been an excuse to avoid studying became a rewarding milestone in Hickey’s life. Just under a year after that impromptu call, he donated one of his kidneys anonymously, also known as an undirected donation, to an individual he did not and still does not know.

“I thought to myself before calling that I could just exit all these tabs, tests and conversations about figuring out time off and just not do it,” says Hickey, the now 27-year-old owner of Pathway Jiu Jitsu School. “I think that’s a common thing that happens before you make a major decision — when you’re comparing staying where you are to making a big change.”

Hickey was well aware while deciding to sporadically forfeit an organ that it would be easier to do nothing at all. In the end, the decision he made to donate his kidney anonymously was not grounded in a debate between easy and hard — it was between right and inertia.

“It was the most common sense, matter-of-fact thing I could imagine,” says Hickey. “The testing tells you if you can or can’t donate, and when I found out I could, there was no downside greater for me than the upside for the recipient.”

Hickey’s organ donation story doesn’t end there. His experience with donating a kidney went above and beyond his expectations — so much so, that on his one-year follow-up of donating his kidney, he asked nurses at the Ottawa Hospital a follow-up question: “Can I donate my liver?”

That marked the beginning of Hickey’s second organ donation —this time completing the work-up and testing process at the Toronto General Hospital — where he eventually donated a piece of his liver undirected in October 2015.

As we are all consumers of what I refer to as “heroization media,” meaning journalism that capitalizes on rare subject matter to chronicle a hero, Hickey’s bare-boned reasoning for donating two organs, both anonymously, might disappoint some.

Hickey’s inability to pinpoint an exact reason that drove him to his extraordinary altruism is a reflection of his inherently strong character. He competed in provincial wrestling competitions all throughout his teen years, was top of his class in high school, and was elected “Head Boy” in his graduating year at Sacred Heart High School, where he continues to coach wrestling to this day.

If there’s one thing that drove Hickey’s decision with certainty, it was the value of spending a few weeks of being uncomfortable as a young and healthy former athlete to help someone who has spent potentially half of their life on dialysis.

An urgent need for living donors

Ontario logged 242 living kidney donors in 2019; in 2020, that number dropped to 171. Many factors come into play on this statistical dwindling. For one, COVID-19 put all surgeries at higher risk, and some living donor transplants were postponed to ease pressures on hospitals and to protect donors and recipients from COVID-19.

Hospitals across the province are however running more smoothly now and, as of Nov. 30, 2021, the kidney transplant waiting list in Ontario sat at 1,070 people.

Dr. Ann Bugeja, Medical Director of the Living Kidney Donation program at the Ottawa Hospital, says that there are some common misconceptions about living kidney donation.

“There are two main risk categories with living kidney donation – the perioperative risks and the long-term risks,” says Dr. Bugeja. “However, a lot of the literature on this is older and things have evolved since then.”

The perioperative risks Bugeja refers to include the risk of death, which comes with any medical procedure, and currently sits at three in 10,000 donors. Infection affects two per cent of living donors, and is treated with antibiotics accordingly. There is also a one to two per cent risk of deep-vein thrombosis from immobilization, which would be treated with blood thinners, and a two per cent risk of getting a small hole in the lung during surgery, which usually seals itself up.

“The flip side, of course, is the benefits,” says Dr. Bugeja. “One of the greatest benefits to the donor is a sense of satisfaction — rarely are there psychological issues associated with donation and donors tend to be very motivated, do very well in the process, and enjoy their experience.”

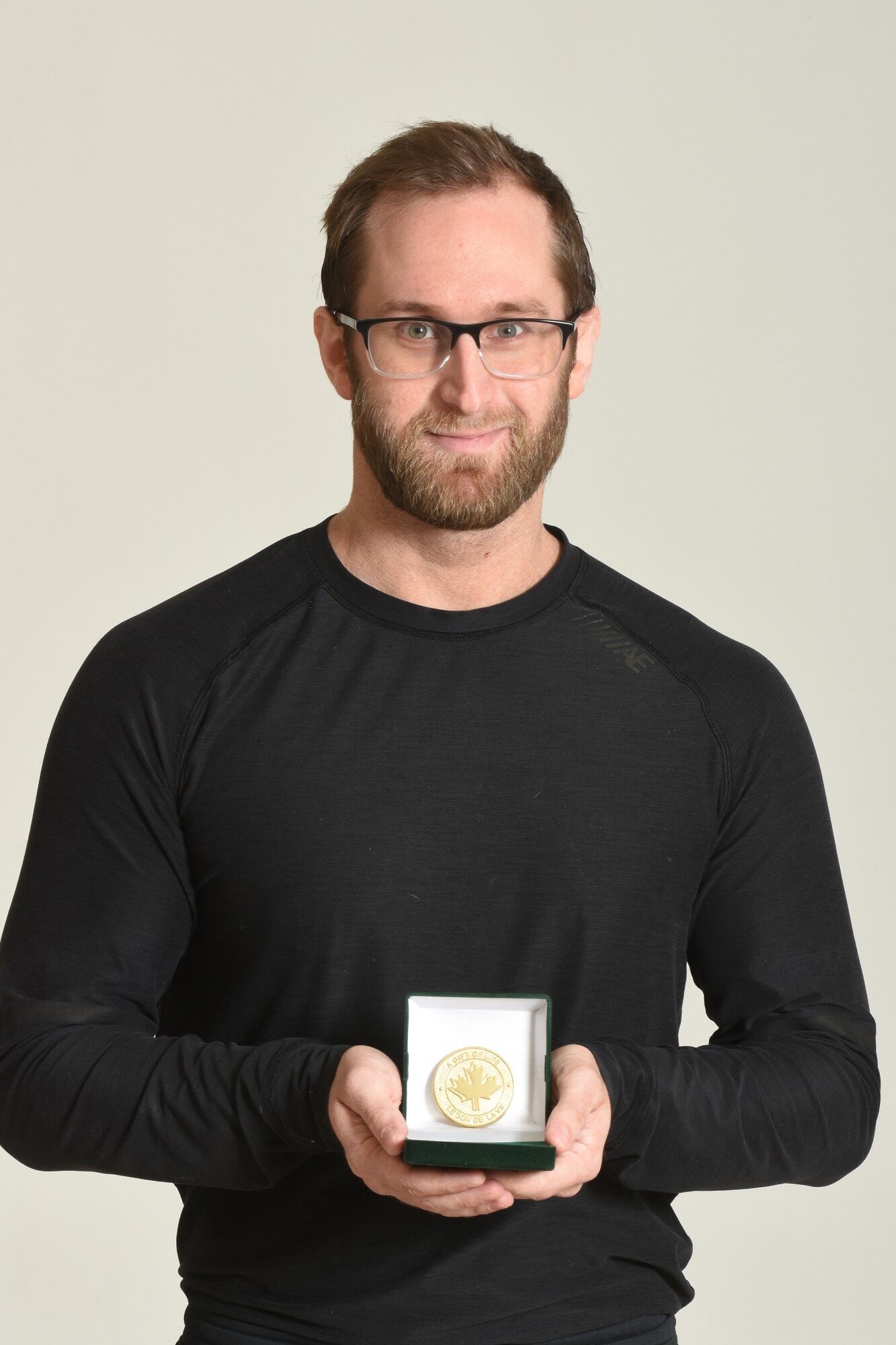

This is clearly illustrated in Hickey’s case, as he is now a two-time recipient of the Trillium “Gift of Life” medallion that is awarded to living organ donors in Ontario.

According to Dr. Bugeja, those who receive a kidney transplant from a living donor after five years have a better chance of their kidney functioning than those who receive a kidney from a deceased donor. Although the gold standard for anyone suffering from kidney failure is to receive a transplant by any means, the living kidney donor can give slightly better results.

The heartfelt gratitude of living organ recipients

Take it from kidney transplant recipient Andre Thibault, 31-year-old support advisor at Shopify in Ottawa and Fanshawe College business marketing student. He hadn’t been to the hospital for anything more serious than a few sport injuries until receiving a call from his family doctor in March of 2019, three hours after going for a routine check-up.

“I was experiencing some serious migraines, so I went to go visit my doctor to see what was up,” says Thibault. “She called me and told me there was something wrong with my kidneys and to go to emergency at the hospital right away.”

That one phone call saved Thibault’s life. After waiting to see a nephrologist at the hospital for more than 12 hours, Thibault received stupefying news from Dr. Brendan McCormick, who Thibault was to spend the next six months of his life with.

“I don’t really know how to tell you this, so I’m just going to say it,” said Dr. McCormick to Thibault. “You have a renal disease called IgA nephropathy, an autoimmune disease that has reduced your kidney function to 25 per cent.”

Thibault sat in mortal fear after receiving this news. He just couldn’t wrap his head around why this would have happened to him — he lived a healthy life, played sports and both of his parents were healthy as horses.

Andre Thibault is back on the road to a full recovery after receiving a kidney transplant from his mother just over a year ago. Photo credit: Tamara Condie

Today, he is fully recovered after a two-year battle with IgA nephropathy, which included four months of dialysis and one kidney transplant, but those two years took both a physical and mental toll on Thibault and his family.

IgA nephropathy is a tricky autoimmune disease that overproduces a protein in the kidneys — IgA — causing inflammation that ultimately damages the kidney tissues. The goal of the initial treatment for the disease is to prevent end-stage kidney disease, which happened to be five months of taking prednisone for Thibault, an aggressive corticosteroid with significant side effects.

“I ran the gamut of side effects from March until about September,” says Thibault. “I was not a fun human to be around — every morning, I would wake up with a swollen face, ankles and hands and couldn’t sit still or control my emotions.”

After being weaned off prednisone, Thibault’s kidney function was looking good for about seven months, until the pandemic hit Ottawa in March of 2020. Thibault began showing signs of inexplicable fatigue and nausea, and by August of that year his bloodwork showed that his kidney function had dropped below 10 per cent.

“As soon as your kidney function drops below 10 per cent, they need to put you on dialysis to prevent kidney failure,” says Thibault. “That was when the preliminary testing my parents did to see if their kidneys could be a match kicked into overdrive.”

Thibault’s first day of kidney dialysis was no less shocking than his initial diagnosis of IgA nephropathy. The doctors implanted a port surgically on his shoulder, and it would protrude from his body around the clock until the end of his treatment. This port inserted a series of rubber tubes in Thibault’s chest — one going into his jugular and another just outside of his heart. This was how Thibault was to receive dialysis for the better part of four months, until his mother donated her kidney to him.

“At first my dad was supposed to donate his kidney to me, but he had some issues with his kidneys that prevented that from happening,” says Thibault. “My mom wasn’t ready for the process to stagnate, so she got tested right away, and less than two weeks later we found out she was a match.”

On November 26, 2020, Thibault and his mother underwent back-to-back surgeries. From 8 a.m. to 12 p.m., Thibault’s mother had her kidney removed. As she was being wheeled into recovery, Thibault passed her while being wheeled into the operating room to have his kidneys replaced by his mother’s donation.

Thibault’s mother saved his life. He knows he is lucky for having access to a family member that was willing to donate a kidney, but appreciates the rarity of his situation.

“At first it was very weird — I could feel it in my abdomen and it was a big physical and mental hurdle for the first five or six months,” says Thibault. “There is now a part of me that stops to acknowledge, every once in a while, that there is someone else’s organ inside of me, and that someone happens to be my mother.”

According to a Canadian Press article, as of 2017, each person in Ontario on the kidney transplant waitlist will spend on average of four years waiting for a transplant. This means that more than 1000 Ontarians will have to undergo dialysis for four years, anywhere between three and seven days a week for hours on end, waking up every day and hoping for a kidney donation.

Being a living donor is not something to be taken lightly, say both Hickey and Thibault. There are risks associated, but the gift of giving in such an intimate context creates an unimaginable gratitude for the recipient.

Hickey sometimes thinks about the fact that there would have been a matter of 100 metres between him and the individual he anonymously donated his kidney to in 2014. However, the jurisdiction of Ontario will not provide the identity of the recipient to undirected donors in order to protect transplant recipients.

“It’s pretty wild to think I was basically next to them and know I’ll never know who they are,” says Hickey. “But I look at it as logical consistency — most people wouldn’t think twice about donating to their mom or sister. That’s someone else’s mom or sister, and they might not have someone who’s able to donate.”

Other than finishing school, becoming a successful business owner of Pathway Jiu Jitsu and learning how to manage his procrastination tendencies a little better, Hickey’s life has not changed much since forfeiting two of his organs. In fact, his preliminary testing for donating his kidney and a portion of his liver provided him with a thorough medical exam that made him feel even more confident about his physical health.

“Mentally, it can be tough, but it was so worth it,” says Hickey. “It’s a weird experience, because it just ends, but I like to remind myself that the abrupt ending of my transplant experience kick-started the rest of my kidney recipient’s life.”