The most memorable moment of my life was when my parents told me to stand up for what I believe. At that time I was a child, playing with dolls and having fun with friends, but as a grew older I realized that we were living in a world where many people faced challenges for standing up for their rights, especially in countries like Turkey—where I’m from—Saudi Arabia and Russia, where innocent people, including members of the press, are stripped of their freedom of expression and put in jail to be kept quiet and forgotten.

Let me take you back to my life six years ago, when I realized that journalism was the best way for me to help and give voice to the voiceless.

On July 15, 2016, Turkey was subjected to the deadliest coup attempt in its history. Several divisions of the army sought to control various parts of the city, including Istanbul, Ankara, and more. The Asian part of the Bosphorus Bridge was blocked by several military tanks ready to shoot civilians trying to cross the bridge. F-16 fighter jets launching missiles at the presidential residence kept residents of the capital up all night.

My parents are part of the civil society movement called Hizmet, the Turkish word for service. It was established by Islamic scholar Fethullah Gulen. Gulen has inspired millions worldwide, making speeches on humanitarian values, peace, prosperity, universal dialogue, and more. He stresses the importance of education and tells his followers to volunteer and establish schools worldwide to “enlighten the youth.”

Movement volunteers do not expect anything in return for their participation; if they do, they are not acting in the spirit of Hizmet. The movement has people from all walks of life: journalists, lawyers, doctors and teachers among them. Hizmet is not a political party or government program. If an individual acts differently from the fundamental values of civic volunteerism, or in other words, “values gain more than her/his actions,” then Hizmet is not responsible for their actions.

In 2016, I was studying international relations at Suleyman Sah University in Istanbul. I decided to spend my summer break with my parents and little brother in Tunisia, where my father was the chairman of the Kheireddine International school. On the morning of the coup, he was in Turkey on business. It was around 10 p.m. when my mother started yelling, “Sevval! Come here, something’s going on in Istanbul!” When I arrived in the living room, the news was on. They announced that military forces were seizing control of the Turkish government.

We were shocked, but I knew it was all orchestrated, and the government would blame the Hizmet movement for the coup attempt. We immediately called my father. He was unaware of what was happening when he received the news. He comforted and reassured us that he would reserve a plane ticket as soon as possible to return home. Hours later, loyal soldiers and police officers stopped the coup attempt with the help of civilians. Around 270 people were killed during the unrest.

A few days later, I realized that I was right in thinking something was odd about this sudden uprising. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that he would approve a decree that extended the period in which police were able to detain individuals and question them with a criminal offence and later get released — and closing Gulen-linked firms. The ordinance allowed the closure of 1,229 foundations, 1,043 private schools, 35 medical institutions, 19 unions, and 15 universities that were all labelled “terrorist organizations.” Unfortunately, my university was one of them.

I told myself that all this was just a nightmare. How can the government be so cruel to its people? I could only worry about my father at that moment and hope he would return to Tunisia safe and sound. We were relieved when, a week following the coup, he got a plane ticket. But it almost wasn’t fast enough, as the government began capturing people working in organizations affiliated with Gulen. My dad remembers a time at the airport when he was standing in line at passport control. “I had a family in front of me. When it was their turn to go through passport control, the authorities suddenly told them that they could not go through because their passports had been revoked for some reason. The family panicked, and I knew they were supporters of Gulen,” says my father. Police instantly took the family into custody. Luckily, my father came home in one piece.

Over time, more and more people were arrested. Among them were my relatives, professors and friends at Suleyman Sah University. My uncle was also detained for teaching at a Gulen-linked school in Balikesir. Doctors, journalists, police officers, public prosecutors, lawyers, businessmen and anyone you can imagine were jailed and tortured for being against the government or sympathetic to Gulen.

For the next five months I was in Tunisia with my parents, at which point I discerned that it would be unlikely that I would return to Turkey to complete my schooling, if ever.

Seckin Ergun, 43, is a Turkish immigrant and long-time journalist currently living in Ottawa. I met with Ergun back in 2017, at an event held in the Turkish Community Centre, after my family escaped to Canada. We kept in contact and he has been a mentor guiding me whenever I needed advice regarding my program.

"Journalism is a public work for the community to learn the truth," says Ergun. Photo credit: Seckin Ergun

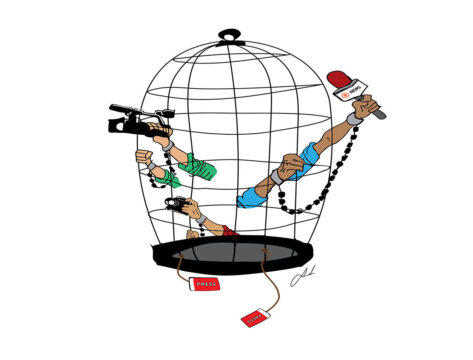

Ergun points out that journalists all over the world are imprisoned for spreading the truth. “This is a sign of direct or covert dictatorial regimes. Even according to the most optimistic figures, 120 journalists are still detained in Turkey. If I hadn’t come to Canada, I would be in jail now,” Ergun says. He expresses his frustration at facing nine years in prison for content he posted on Twitter.

Ergun calls on the United Nations and free western democracies to impose sanctions on countries that do not respect freedom of the press.

“It would be a mistake to expect non-democratic regimes to act otherwise. However, here, especially western civilization, needs to react adequately on this issue,” Ergun continues. He’s certain that “interests manage the world. For example, the European Union and America continue to work with the President of Turkey despite all they have done. The reason is so simple. Turkey accepts tens of thousands of refugees from countries such as Syria and Afghanistan,” Ergun says.

In January 2017, I got accepted to a university in Poland, where I decided to change my program from international relations to journalism, because I no longer wanted to sit back and watch innocent people being tortured, abused and oppressed. I didn’t want to live a life doing nothing to help those who were fired from their jobs for having links to Gulen. I couldn’t stay silent and ignore what the government was doing for their own benefit. I decided to use all my journalistic skills to help people and lend them a voice from that day on.

I knew the path I took was not going to be easy. There are many risk factors that I could come across while doing this job. As of right now, by writing and publishing this story, I’m closing all the possible doors to enter Turkey. I could be targeted by angry crowds, threatened by Twitter mobs, or pressured by government officials. But I do think it’s a job that could help save many lives. Journalism exists to serve the people and hold the powerful accountable. In my eyes, a journalist objectively and accurately narrates a story that has occurred or is occurring based on their observation and findings. One should not forget that “countries where journalists do not do their duty can easily lose freedom and democracy,” says Ergun.

When I tried to renew my passport at the Turkish embassy in Warsaw back in 2017, I found myself being interrogated. The employees were perplexed as to why I had visited so many nations, such as Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar. They also inquired about my father’s employment status and location. It was apparent from all the questioning that we were on their radar. I was unable to get my passport renewed.

After completing the semester, I returned to Tunisia. Tunis’ white villas and condos struck a chord in my memory of Bodrum, Turkey and I felt less homesick. The clear waters, sandy seashores and Arabic cuisine helped too. It’s a nation with strong ties to Turkey but sadly, warning signs were beginning to appear.

In July 2017, my father reserved an early flight to Belgium for a business conference. At the passport check, Tunisian police told him his passport was invalid. The Turkish Embassy had notified the Tunisian officials that my father’s passport was lost and had signed documentation acknowledging it. My father informed the Tunisian authorities that this wasn’t true. They kept him for one hour while trying and failing to communicate with Turkish authorities. They had no choice but to let my father catch his flight, but it was clear something was wrong.

The following day my mother woke me up in panic. I asked her what was going on, but she didn’t tell me anything about my father’s conflict at the airport with the officials. All she stated was that we were moving from Tunisia in two days. I left most of my things, only taking essential items. During our passport check, the police questioned where my father was and when he would return. We assured them that he’d be back in a couple of days, knowing he’d never return.

We knew we had to search out someplace that would give us complete protection against the Turkish humanitarian crisis. Since we had visas, the United States was an option, but it wasn’t the best place for several reasons. So, in August 2017, we immigrated to Canada. While Canada has extreme weather, it gives us more education and health-care opportunities, which are important for my family, as my younger brother and father have health issues.

After coming to Ottawa, it took us three months to settle down. My father started working as a school driver in a transportation service, and my mom and I worked in a local cafe while my brother went to primary school. In 2018, I applied to the University of Ottawa and was accepted into the Journalism program—a joint program with Algonquin College.

Today, I’m a fourth-year journalism student trying to pursue a career that will allow me to stand up for people’s rights. When I think back on my life, I realize how strong I was. I’m glad my family stuck together and have a roof over our heads. We were able to avoid what we thought was our fate. Sadly, many people did not and that’s where I can help them by spreading their story.

Thank you for being the voice of thousands in Turkey, Media and Journalism are both a powerful tool nowadays. So the voice is heard everyone.

Şevval,

Cok guzel bir yazi yazmissin.

Seni tebrik ediyorum.

Bu yolda başarılar diliyorum.