One evening as I drove my friend home from a night of board games, in the comfortable and safe darkness of my car, he asked me, “Have you heard the news?”

In the short time that it took to drive him home, he informed me that our mutual friend had been publicly accused of rape over a popular Facebook social group. The remaining details of this conversation and my drive back home are still a blur to this day.

When I arrived home, I messaged my close friend who told me she had just heard the same news. I combed through the posts on the group only to find out later that this particular post had been taken down by the administrators. With each passing minute, my panic grew more urgent. In some weird, twisted part of my mind, I wanted to defend him. I wanted to read the post so I could at least determine one of two things—either it wasn’t my friend, or it wasn’t rape.

My anxiety peaked when my roommate sent me a link to a blog titled, “My Name is *Anna.” Hesitatingly, I clicked on the link and carefully read her story.

As I read through the devastating and raw narrative she painted, glimpses of the man I had known for two years flashed in my brain. With each word, my heart sunk deeper and deeper into my stomach. The man that she was describing was, without a doubt, my friend. And the thing that he had done to her one night was, without a doubt, rape.

When I first met him in 2013, I found my friend to be a tad quirky and boisterous. But we quickly discovered our common interests and quickly became close friends. It was this version of him; the jovial, sweet guy that I imagined, that Anna had woken up to find raping her after making it abundantly clear she did not want to have sex.

I remember sitting completely still while reading the story and feeling dizzy like I was somehow pacing the floor as fast as I could. It wasn’t until I finished reading that the shaking began and the tears followed. I made a decision that night that was swift and unrelenting: my friendship with him was over.

In the past five years, he was one of the two men I have called a friend who has been accused of terrible things. With him, there was an accusation of rape. With the other; multiple charges related to child pornography and over three years in prison. And with both cases, my heart and mind immediately shut themselves off to these two men, stashing our memories in a place that I rarely (if ever) visited.

Sarah Silverman came out with a statement in November when her friend and fellow comedian, Louis CK, was accused of sexual misconduct. “It’s a real mind fuck because I love Louis, but Louis did these things,” she said. “Both of those statements are true, so I just keep asking myself, can you love someone who did bad things? Can you still love them?”

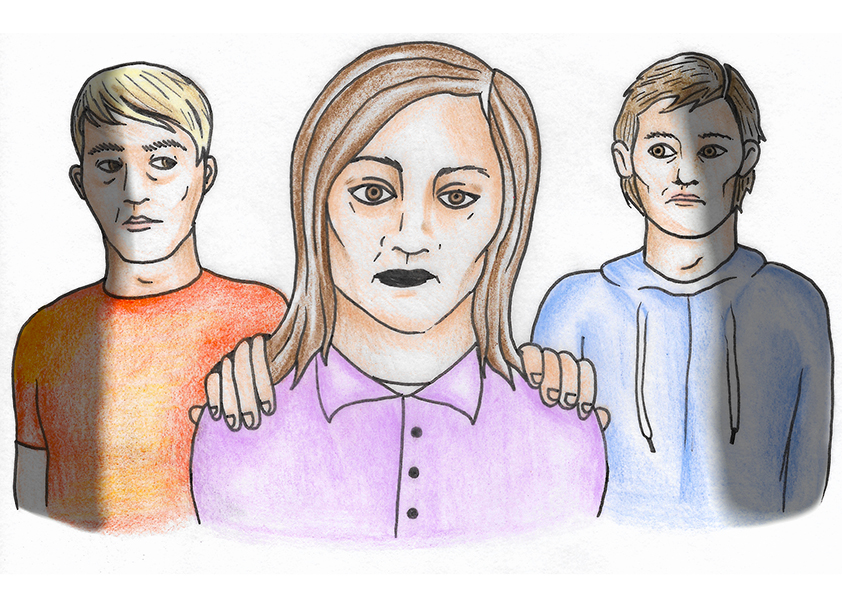

Could I? Did I? When the #MeToo movement began, a confusion lingered in the wake of the grief for all the victims who were coming out, which sparked memories of my own experience. What do you do when you’ve known and loved someone who has done terrible things?

Between 2009 and 2014, Stats Canada reported that one in five sexual assault cases reported by police led to a completed court case. Knowing that there were 636,000 self-reported incidents of sexual assault in Canada during this time, it seems likely that hundreds of thousands of family members and friends of these victims and offenders were also affected by these crimes.

Additionally, sexual assault remains one of the most underreported crimes in Canada with over 80 per cent of incidents left unreported by the victim. Suddenly, the reach of sexual assault jumps from hundreds of thousands to millions.

This made me wonder how many people had a similar reaction to mine: cutting off the loved one-turned -offender completely.

“Reactions to this kind of discovery are different for every single person,” said Amina Doreh, Public Education Coordinator and support worker for the Sexual Assault Support Centre of Ottawa. “The most common ones usually being shame, embarrassment, guilt, sadness, anger and denial. People often hold conflicting feelings and cycle through different stages of reactions.”

This was absolutely true. I could even pinpoint the moments that I had these gut reactions after hearing the news about my friend. Ultimately, my emotions festered into a mixture of deep anger and guilt which became buried and forgotten as I moved to Australia a month later.

Andy’s* story was a different one altogether, but the lasting effect it had on me was almost the exact same.

When I met Andy, I was working as a stage manager for a small-town theatre company in the summer of 2013. Myself and three other students spent most of our summer touring and performing for children in parks and school gymnasiums.

When we weren’t performing, we were attending rehearsals for the theatre’s main-stage shows, watching the professionals at work. Much to my delight, one of these shows was a light-hearted jukebox musical. It was at one of these rehearsals that we were introduced to Andy, the music director.

Right off the bat, I found Andy to be one of the most charming and delightfully witty men I had ever met. He was hugely talented and seemed to radiate “coolness.” I left that rehearsal thinking, “I want to be his friend.”

The following weeks saw the four of us spending more time with him as he gave us music lessons, introduced us to his wife and child and joked around with us when we helped out with a few performances. We admired him. We looked up to him. He was our friend.

When we were told the entire company was to attend an emergency staff meeting, none of us could have guessed why. Shock and devastation dawned upon us as the Artistic Director relayed to us that Andy had been arrested for making and possessing child pornography.

After the initial shock of the news began setting in and my teary-eyed colleagues struggled to resume their work day, some having known him for years, I played back moments I had spent with him over and over again. During the next few days, I searched relentlessly for any signs that I may have missed. A glance. A comment. Something that would dull the shock.

But that moment never happened. Any time we had been around him, Andy had been nothing short of kind, funny and professional.

Within weeks, more details surrounding Andy’s actions and arrest came to light in the media. We found out later that he often approached teenagers online, pretending to be a photographer or model scout. He was arrested at an inn with a 17-year old. When he was finally sentenced in 2015, Andy plead guilty to eight charges including making child pornography, internet luring and exploitation of a person under 18 years.

After a short time, my co-workers no longer spoke of him. Neither did I. The man that I had known faded into the back of my mind, only to be replaced by the monster the newspapers described him as. I felt ashamed to even be thinking about him, so I stopped.

Doreh explains this can be a common reaction. “Often times, people who have experienced this [grief] but have not dealt with sexual violence directly tend to minimize their own feelings,” she says. “They sometimes characterize it as ‘selfish’ or ‘overdramatic’ and not worthy of working through because they were not the ones who were directly victimized.”

Looking back on my collective memories of the entire situation with Andy, I find this to be especially true. Almost immediately after finding out, many of my thoughts and sympathies dwelt on the people closest to him: his wife, child and co-workers of many years. Perhaps it was because of this that my own grief faded quicker into my subconscious and I forgot about him for so long.

As more women and men started coming forward with their horrific experiences during the advent of the #MeToo movement, neither man crossed my mind. I was focused on the victims and abusers whose faces were plastered all over social media. It wasn’t until the loved ones of these accused celebrities started coming forward with statements of shock and grief that I was reminded of my own friends.

In the five years since finding out about both men, the question of love had never even entered my thought process. My reaction was instinctual. They may as well have been dead to me. But watching these influential professionals come out and try to come to terms with their love, it almost felt like a light switch turning on in my head. I did love these men. And maybe, I thought for the first time ever, that’s okay.

Dr. William Marshall, Director of Rockwood Psychological Services, has done research and clinical work with, as well as run treatment programs for sexual offenders in federal prisons for decades. He set up the first treatment program with Corrections Canada in 1973. “Many families cut off the offender, particularly if the victim is a family member, but some do not,” says Marshall. “When the latter is true we try to help the offender understand the best way to deal with this.”

The #MeToo movement has certainly set a new precedent for how society is expected to treat sexual offenders—as outcasts. A new form of social justice has arisen from this movement and it closely resembles social suicide.

This got me thinking about the differences between my individual grief versus societal grief. For instance, my hate and anger towards Andy never extended past the people that I knew and talked about it with.

Though the consequences of Andy’s actions reached an unimaginable number of people by affecting the victims, the victims’ families and friends and his own loved ones, at the end of the day, the global acknowledgment of his mistakes was minimal compared to someone like Harvey Weinstein or Kevin Spacey.

Similar to the way in which I reacted, North American society has shunned these sexual offenders and almost guaranteed that they will never work again or live without shame. These men and women are public figures. Unlike the two men I’d personally known, there are few places these people can now go to without being recognized and without being hated.

“Sex offenders get far longer sentences in the US than in Canada and are given little or no assistance upon release; indeed, in most states they are further punished by imposing absurd restrictions on where they can live, where they can work, where they spend their leisure time,” Marshall says. “Indeed one offender we assessed in a US prison said he deliberately broke the conditions of his release so he could get back to prison because life on the street was way worse than being in prison.”

At the end of the day, there is no clear-cut answer as to the precise way in which we deal with loved ones who have sexually abused another.

Savannah Guthrie, anchor on the Today Show, made a statement about her co-host Matt Lauer after he was accused. “How do you reconcile your love for someone with the revelation that they have behaved badly? And I don’t know the answer to that.”

It’s been five years and I still don’t know the answer to that. I haven’t spoken to either man since their actions were publicized and am only now coming to terms with each situation, much like all of us are doing during these drastically changing times.

As a society, we should feel rage. We should be angry. But we must also allow ourselves to feel sadness and loss. We must remember that these “monsters” were our friends, lovers, family members, neighbours and mentors. Channeling our emotions together into a blind rage towards them and our memories with them won’t help us heal as individuals or as a society.

*Name has been changed