Virtual reality is currently in a state of hectic development and hype. While the innovators and early adopters of the technology are busy creating and destroying virtual worlds, the large majority of the public hasn’t really had a chance to experience virtual reality, because the technology is still too expensive.

This is where Colony VR, a family-run virtual reality arcade and community hub for local VR software developers that’s nestled in the heart of Little Italy, comes in.

Stephan Scherer, co-owner of Colony VR with his partner Rebecca Johnston, started daydreaming and designing a business concept with his family in the Spring of 2016 when the HTC Vive headset was on the verge of release. Stefan and his daughter Thea Johnston, went to a VR demo at Carleton University, where they tried the HTC Vive for the first time.

“They could not stop talking about how extraordinary it was,” said Rebecca. Stefan had been monitoring the VR space for over a decade as an engineer, and this was the first time the technology had impressed him. “He’s a bit of a hard sell.”

Stefan said he was immediately considering how to get the public excited, how to get interest and build a business around virtual reality.

But part of the problem was that the top of the line headsets, with the computer to run them can cost up to $5000, Stefan explained. And you need to be able to dedicate a room to them, since the experiences are room-scale.

All of the affordable VR experiences pale in comparison to the headsets. Google Cardboard and 360-degree video are interesting, but nowhere near living up to the hype of world-changing technology, and often disappoint people who get caught up in the hype. And they often make people sick because of bad motion tracking.

The potential of virtual reality as a world-changing technology can really only be felt in the high-end headsets like the HTC Vive and Oculus Rift, which are a lot less accessible to the general public.

During the summer of 2016 the technology was mostly in the hands of early adopters and developers. Stefan was seeing the excitement at the OttawaVR community meet-ups, which drew people from Ottawa’s tech industry, and the Universities and Colleges. The discussions and demos at these meet-ups lead to some successful local developments.

John Gagne, CEO of Ottawa start-up Brinx Software and main organizer of the OttawaVR meet ups, teamed up with Algonquin College programming students to launch MasterpieceVR, a professional painting and sculpting app. And Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, a cooperative virtual reality game about defusing bombs, grew out of the meet-ups and has since become a highly acclaimed VR game.

But these successful start-ups got busy quickly and the information about what was working was no longer filtering back to the community.

So the family bought a headset and played around with the technology for the summer, daydreaming until a business concept formed.

They settled on a dual-business model; a video arcade in the evening to get the public excited about this new technology, and a space during the day for local developers to discuss, test, and demo their creations.

“There’s always risk because we’re self-financed,” said Rebecca. But after playing with the numbers they figured the worst case scenario was the equivalent of one year of an MBA program for her daughter Thea.

“It’s a bit of a no-brainer,” Rebecca added. “It’s a laboratory for Stefan to leverage his own hardware and software development, and it’s an opportunity for Thea and our eldest son Eric to gain some real tangible business experience.”

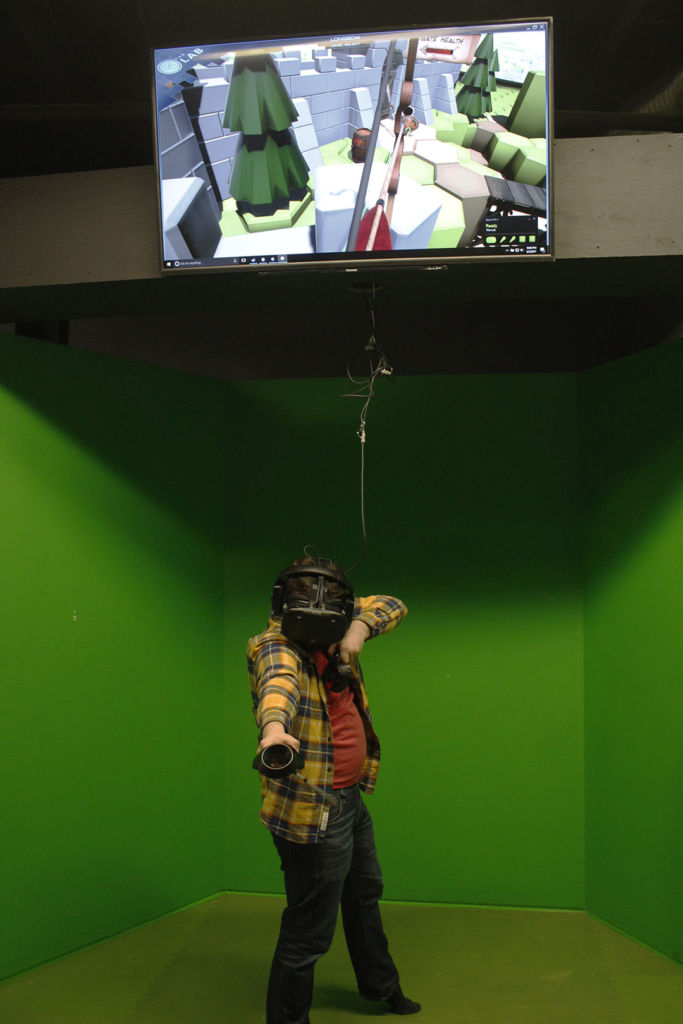

Stefan rented a warehouse in Little Italy, and started engineering the space with the help of his children. They bought six HTC Vive headsets and computers to run them, and built room-sized, moveable playing booths that people could rent.

The initial set up was a big investment, but Stefan said that the physical space and the staffing around a business is the majority of the cost. “It’s not really something you can scale,” he said.

They kept the industrial feel to accentuate the fact that this technology was emerging and painted the walls grey so that they could easily change the look to accommodate different types of community events.

“Part of what we designed here was the opportunity to just observe people using the technology,” said Rebecca, “and to be open to what the pain points were, what the dynamics of the gameplay were, how people were interacting with the technology.

So far they’ve spent over $3000 on games, and estimate that only about 10 per cent of the games are really any good.

Thea, who runs the arcade in the evenings, has tested over 200 games and experiences to figure out which ones are good and she curates the experiences depending on individual interests, ages and comfort levels.

Many games have confusing controls, nauseating movements, and awkward game design. “It’s like Battle Royale right now in terms of what parts of the controllers are going to do what,” Thea said. “If feels like I’m watching natural selection.”

Thea keeps track of the feedback she gets from customers, and what she learns as she’s testing the games so that this information can go back to Ottawa’s developers so that they don’t repeat the mistakes of others.

“Maybe it won’t last too long because the equipment will come down in price,” said Stefan, “but for the next little while as we figure out what other kind of business we can do around it, what kind of software is needed, or what kind of hardware can we do that augments the arcade experience, we can do this and observe people as they’re enjoying it and learning about virtual reality.”