Orienteering is a sport where skilled navigation is essential. Excellent endurance is important, but an ability to read a detailed contour map of a forest and plan the quickest path from marker to marker, while running, is what will make a competitor stand out.

Jeff Teutsch, coach of the Canadian high performance junior team says that since he started competing in 2008 there has been a consistent growth in popularity in the sport in Ottawa and across Canada.

“We’ve come a huge way to where we are now,” says Teutsch. “We’ve got a high performance coach in each of the major city centres.”

Ottawa’s competitive orienteering athletes are currently training for Canadian Championships in August 2017, which will be held in Perth, Ont.

“The goal is really to move up from one tier to the next in the world rankings,” says Teutsch. The men are currently in the third tier and can send one man to the World Championships for each division. If they get into the second tier they will be able to send two men to each division. First-tier countries get to send up to three athletes to the World Championships.

Canada’s top orienteering competitor is Ottawa’s Emily Kemp, who finished fourth at last year’s World Championships in Sweden. Kemp is ranked seventh in the world and is currently living and training in Finland. Canada’s top men orienteerers, Teutsch says, are aiming for 40th at the World Championships.

To compete at the highest levels there are three main aspects to master in the sport; the physical endurance, the map-reading skills and the psychology.

It’s off-season right now, so the national team is working on these elements of orienteering in unique ways.

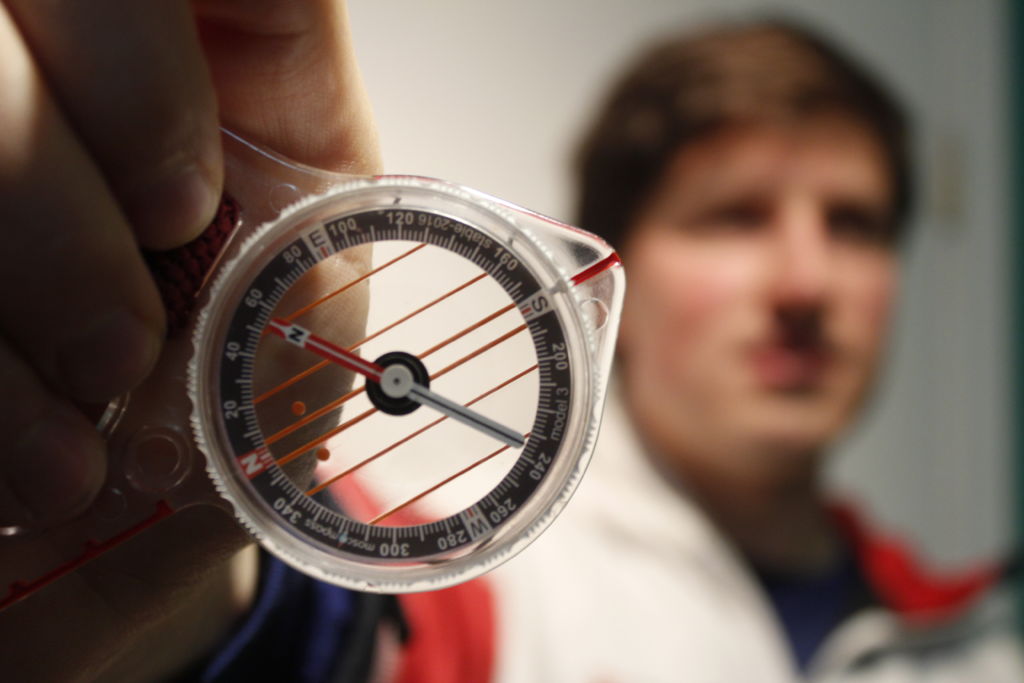

To keep their physical endurance up, members of the high performance program go out on weekly runs through city neighbourhoods with street maps in hand. They are used to much more complicated maps with elevation contours and features such as rocks trees and rivers. To keep the city exercise somewhat challenging they remove all the features from the map except for northern lines. It doesn’t necessarily improve their map reading skills but it keeps them used to running with a map in hand.

The experts say that the physical side is slightly more important at the elite level, explains Teutsch. “You get to the elite level and all the guys are really high map-reading level, so everything then comes down to the physical; your speed, your endurance and your ability to run through the woods.”

But it takes a long time to get good at reading the maps at the level of elite competitors. “It’s just years and years and years of doing it,” says Teutsch. “Three or four times a week.”

To practice their map-reading during the off season, some of the members of the high performance team get together online to play an orienteering video game. “What I find interesting about it is you still have to be very focussed. You get distracted and just like out in the field you keep running and realize you don’t know where you are anymore,” says Teutsch.

Understanding maps and terrain becomes very important for international competition. There is an international standard for the maps, says Teutsch, but small differences in interpretation by map-makers, as well as differences in terrain between countries makes it tricky for competitors.

To make international competition fair, the organizers of the competition must post old maps online so that competitors can study them and get used to the minor differences.

Teutsch says he took the junior team to Switzerland a week early last year to acclimatize them to the high altitude and to figure out the maps and the terrain. “When we saw those maps a the world championship races it wasn’t a total shock,” Teutsch says.

They studied those old maps and drew some courses on them trying to plan the fastest route on paper. But the athletes are not allowed to got to the forest to practice before the races.

“The areas are embargoed,” says Teutsch. “It’s an honour system. It’s a chunk of forest, so they can’t really stop anybody from going in. But no ones really worried about it.”

The final thing that the high performance competitors have to contend with is the unique sport-psychology of orienteering. There are a few elements of the sport that can limit certain competitors.

One is the distraction of seeing someone else in the forest when you run your race. “You start thinking, ‘did this person catch up to me, or did I catch up to him?’ explains Teutsch.

Any time a competitor is not focussed on exactly where they are and where they are going, they can get lost.

“That’s a technical mistake,” explains Teutsch, “but the psychological side is trying to recover from that and reset yourself. If you’ve planned ahead but after making a mistake and arriving at a flag from a different direction you forget to correct your plan and you turn in the wrong direction.”

The ability to reset quickly can make all the difference in a race.