On a Friday afternoon in February, as downtown Ottawa thaws out a little after a record-breaking one-day snowfall earlier in the week, Liam Mooney sits in the shared lounge space of his company’s Chinatown headquarters wearing a faded green Tommy Hilfiger tee-shirt and jeans.

He’s backlit by the large south-facing window which overlooks a rooftop patio—the site of many parties where some of Ottawa’s creatives and young businesspeople intermingle during the warmer months.

In the back room, he’s surrounded by plants. It’s a Jackpine thing.

His three-year-old company—which offers corporate branding among its services—has used plants as a major component of their recent web- and HQ-re-vamping.

The 30-year-old, who is also a part-time instructor at Carleton University, is the CEO of Jackpine, a “creative counsel” agency. The creative consultation industry is one invented by Mooney and his team, and the above-quoted description is proprietary to Jackpine.

Other than himself, Jackpine is home to eleven full-time employees. They also contract out to about 15 to 20 different independent specialists every two weeks. On this particular afternoon, they’re all working away collaboratively on several ongoing projects, while also working on a few pizzas from La Favorita.

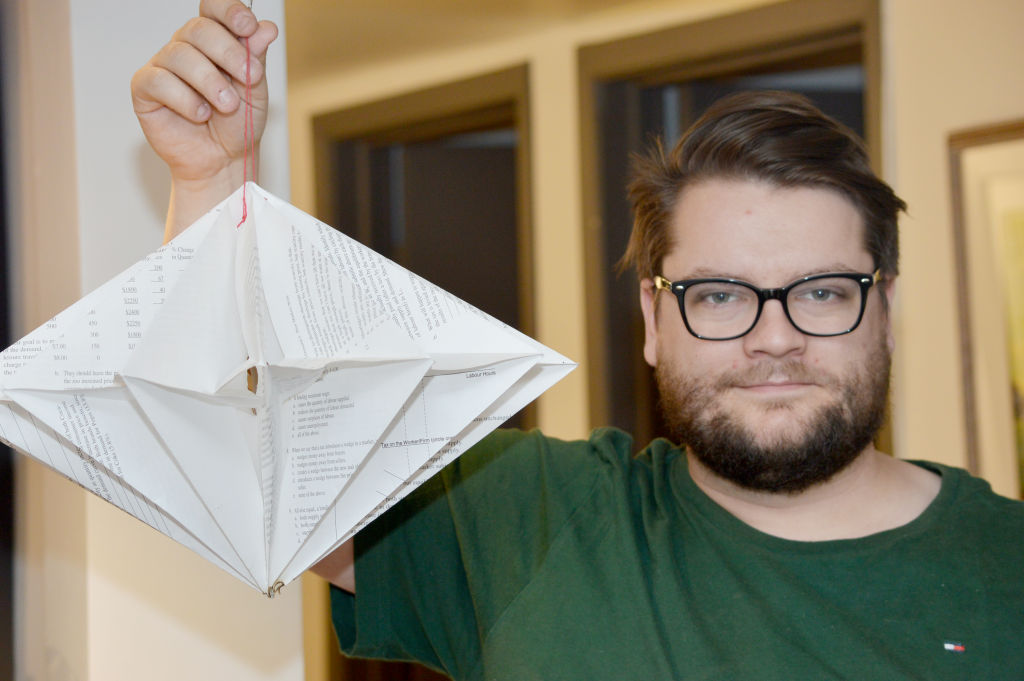

His company does not follow a traditional approach to the services they offer their corporate clients. This fact is perhaps best illustrated by the paper craft which hangs over the main workspace in their open concept offices.

It was given as a gift to Mooney by a job applicant upon his interview. An economics grad, he had made it from one of his textbooks.

It was from the chapter about how markets work. The applicant was hired.

Jackpine doesn’t accept limitations. Services include traditional items such as graphic design, public relations, illustration, industrial design and web design/development—as well as new-school services such as interactive installations, motion graphics and placemaking and urban strategies.

The fresh, new, multi-disciplinary approach to corporate solutions is definitely working.

“We’re a creative counsel firm, and nobody knows what that means because we made it up,” he says. “But that’s what we think we do. We would tell people we’re a multi-disciplinary design firm, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, so you do graphic design?’ and I’ll say, ‘Well, yeah, of course,’ we do all sorts of stuff, though.”

Their broadly-defined business model is of great benefit. They have the talent among their staff to deliver such things as a traditional advertising package, for example, if a client requested it.

But Mooney and his team prefer to ask bigger questions (which tend to yield bigger results).

“We’re looking at a candy company out of Montreal, they have locations in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. It’s like: ‘How can you take us to the next level?’ It’s not about having some YouTube video or Instagram thing, maybe there is some bigger question, and maybe it’s about thinking about how food and beverage—in the past—has been designed to create desire.

You know, the Big Mac comes in a box, now all of [McDonalds’] sandwiches are served that way; the Coca-Cola bottle has that flourish, that’s modeled after this dress and that has become an iconic shape which helps drive their brand character, and to intrinsically connect it to American culture and cement the notion in people’s brains.

So rather than think about some graphic we can make—which might be a part of the mix and something which must be executed at some point—but what is it we could do to create desire for this company? And how can we make a product out of what they have? Maybe it’s just as simple as taking one of their best products and re-imagining how it’s packaged and put together so that it stands out on its own.

Think about Beau’s—that bottle is ingenious, that’s part of the whole thing. It’s an archetype, all of a sudden you have to merchandise that bottle separately from all of the others in the store because it doesn’t stack with the other things, it’s in its own category. Every other beer six pack looks the same.

We have people here who have backgrounds in industrial design and architecture. People who have degrees in this stuff, we’re not just looking to make something like a graphic for someone.”

Beyond the considerable success Jackpine has seen in the various campaigns for their impressive clientele—which includes Postmedia, the Canada Council for the Arts, Claridge Homes and many more— it is also profitable.

But lean. Mooney believes his clients appreciate their simplicity.

“If you look at our growth year after year, the trend is up,” he says. “We grew 70 per cent after our first year, this year we’ll be at over 150 per cent growth. The cost of running the business is expensive, but we’re lean. We don’t overspend, we rent in Chinatown; a lot of established firms have really nice spots in really nice neighbourhoods.”

The company’s approachability (as illustrated by their humble setting and outlook on office culture) and genuine interest in local arts have made it a bit of a nucleus for creativity in the capital. Albeit a discerning one.

“We have met all sorts of people, our studio is open, people walk in and we want that to happen,” he says. “We’ve met so many people from different sectors and industries. We don’t blindly cheer for everything, we celebrate the cool stuff and have fun. But serve it up in a way that isn’t pretentious or distancing ourselves from anyone.”

When the arts and business typically intersect, it is often a meeting between people with disparate agendas. It’s an age-old disconnect—the work of creatives has been undervalued by hardnosed business-types since long before even the Mad Men era.

At Jackpine, however, creativity is actually appraised a little higher than that of business astuteness. And their sense of place is of utmost importance, too.

And it all connects: “We have a strong sense of place. We really feel connected to the community because they have really helped us become what we are. There are so many people’s fingerprints on this company over the last three years or so,” he says. “[And] the national capital has a role to play in defining Canadian design and arts, and there’s room for that—that should be a part of the Lebreton Flats proposals. We care a lot about being here. We love being here.”

Jackpine makes a concerted effort to contribute to the efforts of other local artists and businesses in eliminating Ottawa’s reputation as a boring city.

Such efforts include the projects of Jackpine Labs, such as the Winterlude sculpture, “Jack the Yeti”, “613 day”, a celebration held on June 13 (6/13), the brainchild of Creative Director, Emma Cochrane; and various short films and pop-up art installations.

There’s also Shoufen, a monthly talk hosted at Jackpine’s office, which brings in an inspirational thinker or tastemaker from Ottawa, Canada, or abroad, to discuss ideas.

In simple terms, Jackpine is in its own category. At least in the capital.

“Remove Shopify and a couple of others from the equation,” he says, “and it’s really rare for companies to be social in that sort of a way. We love emerging culture, there’s lots of great shows happening and lots to celebrate and expose people to… We really like engaging with the public, sharing our energy. Making impractical dreams a reality.”

The future holds more of the same, just ramped up a little. They’re rolling out a campaign in the National Post and other subsidiaries under their umbrella; there’s “Percy Station”, a pop-up, on-street collaboration with architecture firm Atelier Ruderal and the City of Ottawa; and a Jackpine musical.

Plus a few other top-secret projects which will undoubtedly get some attention.

As for long term goals: “Staying alive,” he says. “Fighting through a tough economy. Overcoming adversity as a young company. Developing proper channels and systems to deliver the best quality creative counsel we can.”

There are an abundance of possibilities in the years to come, especially as Ottawa expands. Jackpine will continue to stay engaged, genuinely interested in new ideas, and employing bright young creatives.

As Mooney says, due to economic circumstances and more, there exists a lot of talent which has gone un-activated. There are smart young people out there with entrepreneurial spirit and innovative ideas, they’re looking for opportunities—companies like Jackpine are right there with them, and willing to give them an eager audience.

Their doors are open.

On this particular weekend, they’re about to celebrate another work week of collaboration and innovation—and Mooney’s 30th birthday. An employee has just shown up with a case of beer, which they want to put in the newly-acquired vintage Pepsi machine, but it’s not up and running just yet—plus it will probably be emptied pretty quickly.

The office is decorated with several found, or repurposed, objects—yet another testament to Jackpine’s untraditional approach to business and aesthetics.

“If we think about creative processes in a different way,” says Mooney, “and what our clients need in a different way, then I think we’ll succeed.”

Correction: architecture firm Atelier Ruderal was confused with the cutting edge Ottawa restaurant.